On an encounter with the bureaucracy

The Civil Secretariat is the old British center of the city of Lahore. The old imperialists constructed this bureaucratic center to maintain power over the city, connected to the Mall Road and the various centers of capital and industry in the city. The bureaucracy flows from this space still, as different types of government departments and provincial ministries sit at its grounds. On this day, I walk into a series of constructions, reconstructions, and demolitions across the secretariat. The Punjab Archives–located in the erstwhile church building now housing a cenotaph dedicated to Anarkali–is being uprooted.

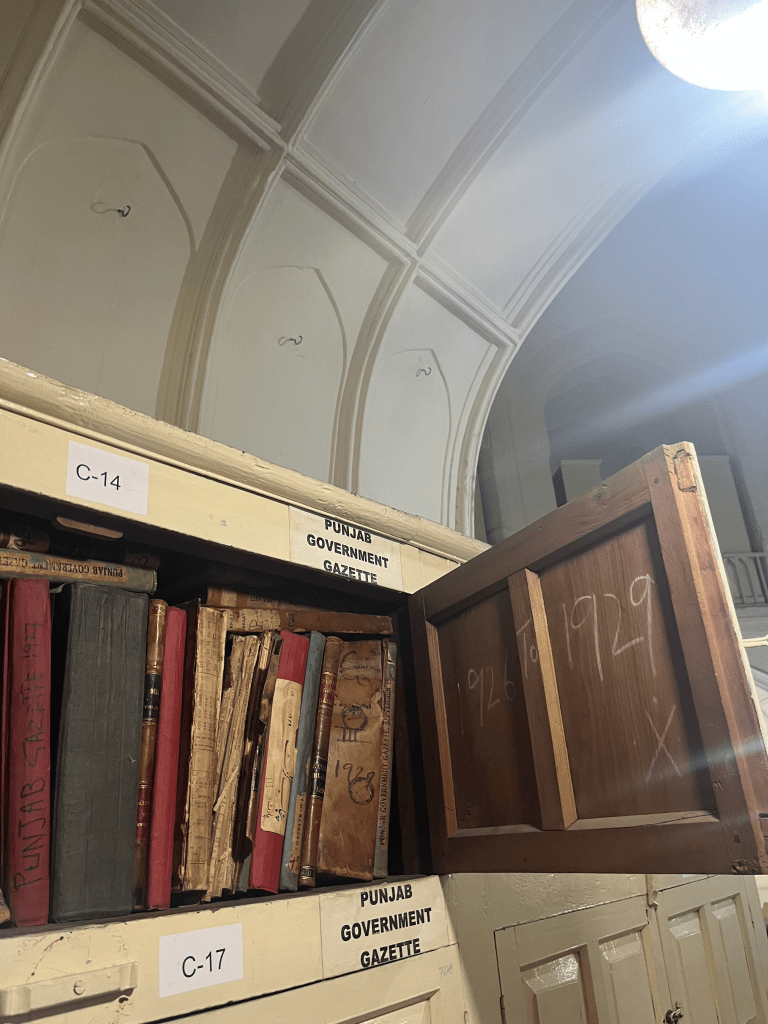

A new Director General has decided to make the tomb his office. He will be out of his position next month. White painted buildings are being demolished, the soft innards exposed everywhere; the offices are nowhere to be found. Construction workers, who here are more like demolition workers, use axes and hammers to bring down the old white walls, fitting to replace them with large lawns. The haphazard transference of archival material means that my questions around Jain Mandir and other temples across the city are roundly ignored. The archival records of the Punjab Archives are being removed from the specially made archival boxes to a comically small building, one which is surely not large enough to hold all the material. The construction dust and storage will probably leave its mark on the records.

I go into the Shrines Department of the Auqaf, where the Director General tells me he came into office last month and is still gaining control of what exactly his portfolio is. He cannot confirm if Jain Mandir falls into his hands. Another worker says that of course it does; in fact, its sister org the Evacuee Trust Property Board controls every last non Muslim building and land in the province. These offices sit at the top of the civil secretariat, guarded and well-maintained rooms. But the lack of information is astounding. The constant turnover at the bureaucratic level is severe; the absence of institutional knowledge is obvious. Over the years, I have been led through a maze of stunning opaqueness and lack of answers to the questions on the maintenance and preservation of heritage. Today, I descend to the basement.

I walk into the smoky office marked as the engineer’s office. A mustached man in fitted shalwar kameez waits at the center. He takes a long drag of his cigarette. The man is surrounded by ten lackeys, sitting in two identical rows opposite each other. The winter sun enters through the window and illuminates his face, making a spectacular show in the drab basement. He ushers me in and asks my purpose. I go into the same spiel, this time very self-conscious of the small audience assembled before me.

“I am a student researcher looking for details around the restoration of Jain Mandir and the surrounding area. I want to know–”

He stops me in the middle. I am a little nervous that I have said something wrong or I have revealed my sympathies with the Hindus.

“I am the one responsible. I did it”

I am taken aback by his admission and ask for clarification. He says that he as the project engineer of the Auqaf Department handled the repairs, restoration, architectural plan, epigraph writing, and more of the Jain Mandir site. He has worked there 30 years, outlasting numerous regimes of power and immune to the machinations of powers at the higher levels. He takes a hard look at his calendar and asks me to come back Monday at 9 am sharp. He will give me all the information I need. The lackey’s eyes follow me on the way out.