The largest temple complex in Lahore. Damaged in 1947. Demolished in 1992. Rebirthed in 2022.

What happened?

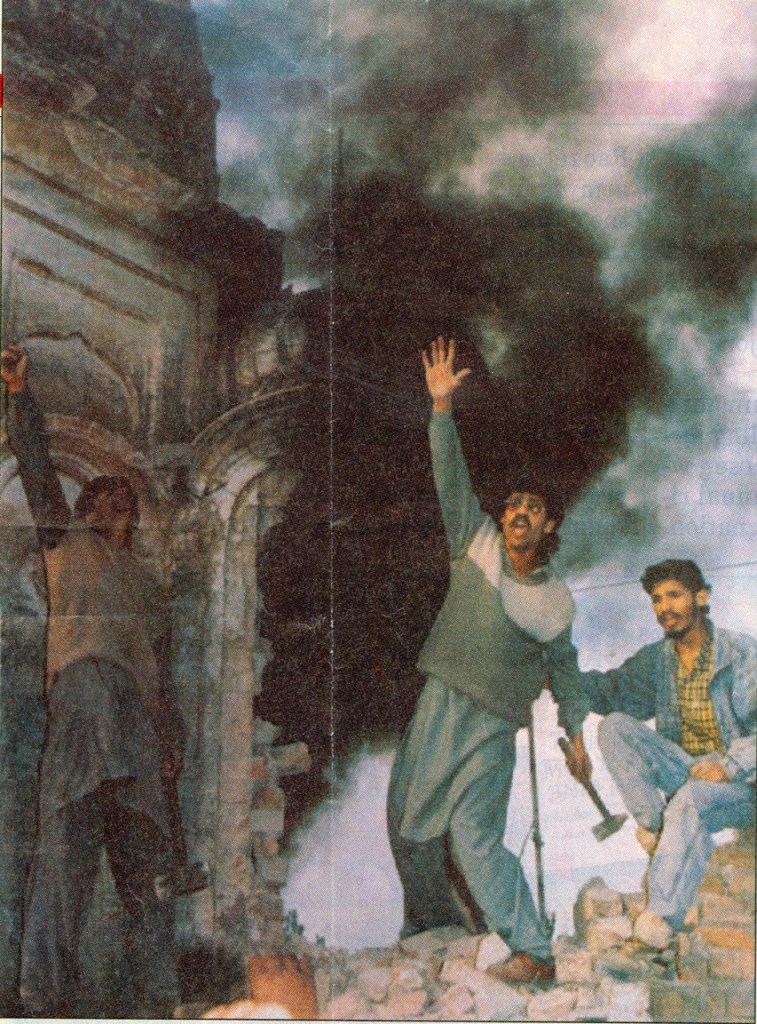

Ayodhya burns on the morning of Sunday December 6th 1992. A RSS-led mob storms the Babri Masjid mosque and lays siege to the 16th century structure. Brick by brick, using hammers, axes, and other makeshift weapons, the Hindutva mob destroys the mosque complex, claiming it as the mythical site of Ram’s birthplace. A saffron flag whirls on top of the mosque’s dome before it too collapses.

In a lighting hostage-taking event across the border, rioters in the city of Lahore descend on the aging mandirs sitting dotted across the urban landscape. Brick by brick, using hammers, axes, and other makeshift weapons, these mobs destroy Hindu and Jain temples, most prominently Jain Mandir, the largest temple complex in Lahore. Unlike in Ayodhya, the mobs in Lahore bring in cranes and bulldozers to collapse the structures of the temples. In a turn of fate, the bulldozer would later become a prominent symbol of the Hindutva class in later years, symbolizing the great destructive power of the vehicle.

Rioters destroy an unidentified temple in Lahore, Pakistan on December 6th 1992

This tit-for-tat violence embodies hostage theory–the foundational ideology of the post-partition states: the Hindus of Pakistan and the Muslims of India are each owed respective majoritarian protection lest the minority population on the other side of the border is harmed. As Zamindar explains, “the logic of the hostage theory tied the treatment of Muslim minorities in India to the treatment meted out to Hindus in Pakistan.” Therefore, when one minority population is harmed, the other population is in danger, a stark reminder of the specialized citizenship matrix for Pakistani Hindus and Indian Muslims. What unfolds is a story of heritage and contestation of the past.

“The logic of the hostage theory tied the treatment of Muslim minorities in India to the treatment meted out to Hindus in Pakistan”

Zamindar, Vazira Fazila-Yacoobali (2010). The Long Partition and the Making of Modern South Asia: Refugees, Boundaries, Histories

In India, the rise of the Hindutva ideology has meant that any sense of Muslim past and Islamic stake over India must be uprooted. The very sense of Indian identity rests on the Muslim invasion theory–that Islam does not belong to the Indian subcontinent and its adherents usurped the so-called indigenous fabric, an indigenous fabric found in Vedic traditions, namely Hinduism. In a stunning turn of the conceptual frame of “decolonization,” the recovery of a Hindu past is linked to unmooring of the presence of Islam around India.

Babri Masjid is the most crucial example; the fascist Modi government opened the Ram Janmabhoomi Mandir in January 2024 on the ruins of Babri Masjid. The inauguration of Ram Mandir also rests on a project of bureaucratic–legalistic and archaeological grounding enshrined by the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI), which concluded that there was evidence pointing to the presence of a “non-Islamic” structure beneath Babri Masjid, and preserved by the Supreme Court of India in a 2019 decision that awarded the disputed land to Hindus.

In neighboring Pakistan, a similar project tries to differentiate an Islamic past from a Hindu one. Negotiated with key reference to its neighbor, this historical narrative has similarities to the Hindu nationalist narrative: Islam came from outside the Indian subcontinent and lays its historical reference to 9th century Arabia. The monotheism of Muslims was always distinct from the polytheism of Hindus, no matter the various assimilationist practices across the subcontinent or the syncretic methods specific to the subcontinent related to the spread of Islam.