The renovation of Jain Mandir in 2023

On December 5, 2021, a day before the 29th anniversary of the Babri Masjid demolition, the Supreme Court of Pakistan ordered that Jain Mandir in Lahore be rebuilt and repaired (along with nearby Valmiki Mandir). This was followed by a series of bureaucratic interventions that completely transformed not just the remaining turret, but the area around it as well. Plans for the Orange Line Metro, Pakistan’s first rapid transit line, passing through the main thoroughfare ignited discourse around heritage and preservation in 2016.

The Punjab Antiquities Act stated that all work within 200 feet of buildings of historical value was illegal, and thus the Lahore High Court ordered suspension of all Orange Line work, also submitting other buildings like Chaburji. Though there were some false reports that Jain Mandir’s remains were completely destroyed in 2016 following the Orange Line’s construction, the authorities actually built a boundary wall around the remains and expropriated the rest of the property to build the flagship Orange Metro Line station: Anarkali. Places like the shrine of Mauj Darya were severely damaged during this development.

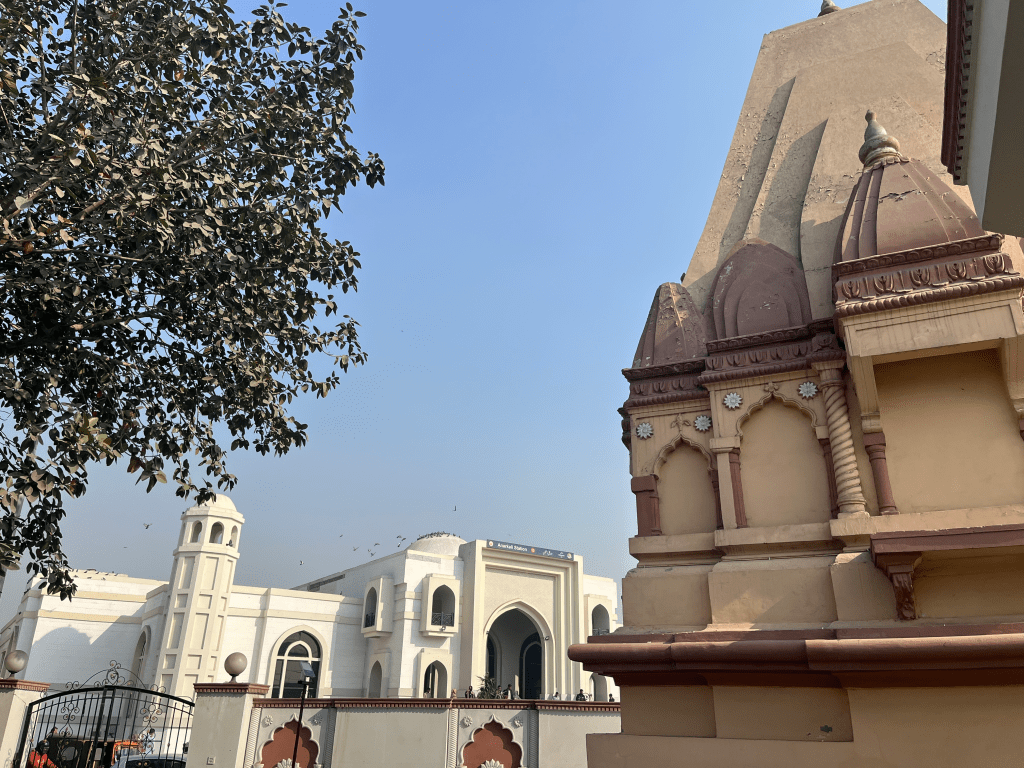

Following the 2021 order, the Evacuee Trust Property Board (ETPB) quickly made plans to repair the temple. The turret was put on stilts, the boundary wall repaired, and a layer of plaster applied to the building. The top part of the turret, the shikhara’s mountain peak, was remade entirely. The decaying part of Jain Mandir was covered with plaster and then stucco.

Traditional historiography assumes the past can be objectively documented, but hauntology suggests memory is palimpsestic—layered with erasures and returns. Jacques Derrida says as much in Archive Fever. Archives don’t just preserve memory, they are sites of repression and spectral returns. What is not archived (e.g., marginalized voices) haunts the official record. This abandoned home, the abandoned temple represents an architectural ghost, materializing loss. Its decaying carcass, despite bureaucratic neglect, connoted an authentic loss of power and a loss of home. What then is the stuccoed Jain Mandir but a zombie, a body conjured alive past its death?

Unlike preserved heritage sites that often present a polished version of history, ruins resist closure. Their decay symbolizes the passage of time and the fragility of memory itself. But the ETPB’s intervention interrupted that instability and did what Edensor calls “resignification,” a process “driven by desires to frame their pre- servation with a singular, legible narrative – [risking] the erasure of other, messier, memories and forms of experience” (Desilvey and Edensor 2012). The affective power of the ruin, one that evokes nostalgia, melancholy, or wonder, making memory an emotional and sensory experience rather than just an intellectual one, is transmogrified by the bureaucracy into a new affective experience. Jain Mandir is now situated as a monument next to a man-made park, an ahistorical centerpiece to a roundabout opposite the busiest Metro station in the city.

Field Notes

-

Bureacracy and heritage

On history and the archive